|

The different

forms of Buddhism can be understood by becoming familiar with

the two major schools that arose out of the Buddha's basic teachings:

The two

major schools of Buddhism, Theravada and the Mahayana, are to

be understood as different expressions of the same teaching

of the historical Buddha. Because, in fact, they agree upon

and practice the core teachings of the Buddha’s Dharma.

And while there was a schism after the first council on the

death of the Buddha, it was largely over the monastic rules

and academic points such as whether an enlightened person could

lapse or not. Time, culture and customs in the countries in

Asia which adopted the Buddha-dharma have more to do with the

apparent differences, as you will not find any animosity between

the two major schools, other than that created by healthy debate

on the expression of and the implementation of the Buddha's

Teachings.

Theravada

(The Teachings of the Elders)

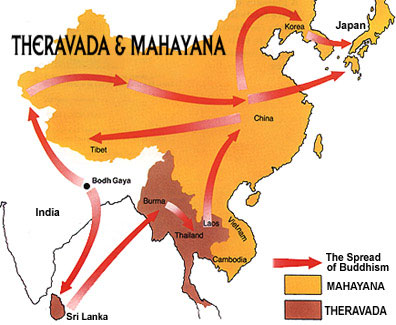

In the Buddhist

countries of southern Asia, there never arose any serious differences

on the fundamentals of Buddhism. All these countries - Sri Lanka,

Cambodia, Laos, Burma, Thailand, have accepted the principles

of the Theravada school and any differences there might be between

the various schools is restricted to minor matters.

The earliest

available teachings of the Buddha are to be found in Pali literature

and belongs to the school of the Theravadins, who may be called

the most orthodox school of Buddhism. This school admits the

human characteristics of the Buddha, and is characterised by

a psychological understanding of human nature; and emphasises

a meditative approach to the transformation of consciousness.

The teaching

of the Buddha according to this school is very plain. He asks

us to ‘abstain from all kinds of evil, to accumulate all

that is good and to purify our mind’. These can be accomplished

by The Three Trainings: the development of ethical conduct,

meditation and insight-wisdom.

The philosophy

of this school is straight forward. All worldly phenomena are

subject to three characteristics - they are impermanent and

transient; unsatisfactory and that there is nothing in them

which can be called one's own, nothing substantial, nothing

permanent. All compounded things are made up of two elements

- the non-material part, the material part. They are further

described as consisting of nothing but five constituent groups,

namely the material quality, and the four non-material qualities

- sensations, perception, mental formatives and lastly consciousness.

When an

individual thus understands the true nature of things, she/he

finds nothing substantial in the world. Through this understanding,

there is neither indulgence in the pleasures of senses or self-mortification,

following the Middle Path the practitioner lives according to

the Noble Eightfold Path which consist of Right View, Right

Resolve, Right Speech, Right Actions, Right Occupation, Right

Effort, Right Mindfulness and Right Concentration. She/he realises

that all worldly suffering is caused by craving and that it

is possible to bring suffering to an end by following the Noble

Eight Fold Path. When that perfected state of insight is reached,

i.e.Nibanna, that person is a ‘worthy person’ an Arhat.

The life of the Arhat is the ideal of the followers of this

school, ‘a life where all (future) birth is at an end,

where the holy life is fully achieved, where all that has to

be done has been done, and there is no more returning to the

worldly life’.

Mahayana

(The Great Vehicle)

The Mahayana

is more of an umbrella body for a great variety of schools,

from the Tantra school (the secret teaching of Yoga) well represented

in Tibet and Nepal to the Pure Land sect, whose essential teaching

is that salvation can be attained only through absolute trust

in the saving power of Amitabha, longing to be reborn in his

paradise through his grace, which are found in China, Korea

and Japan. Ch’an and Zen Buddhism, of China and Japan,

are meditation schools. According to these schools, to look

inward and not to look outwards is the only way to achieve enlightenment,

which to the human mind is ultimately the same as Buddhahood.

In this system, the emphasis is upon ‘intuition’,

its peculiarity being that it has no words in which to express

itself at all, so it does this in symbols and images. In the

course of time this system developed its philosophy of intuition

to such a degree that it remains unique to this day.

It is generally

accepted, that what we know today as the Mahayana arose from

the Mahasanghikas sect who were the earliest seceders, and the

forerunners of the Mahayana. They took up the cause of their

new sect with zeal and enthusiasm and in a few decades grew

remarkably in power and popularity. They adapted the existing

monastic rules and thus revolutionised the Buddhist Order of

Monks. Moreover, they made alterations in the arrangements and

interpretation of the Sutra (Discourses) and the Vinaya (Rules)

texts. And they rejected certain portions of the canon which

had been accepted in the First Council.

According

to it, the Buddhas are lokottara (supramundane) and are connected

only externally with the worldly life. This conception of the

Buddha contributed much to the growth of the Mahayana philosophy.

Mahayana

Buddhism is divided into two systems of thought: the Madhyamika

and the Yogacara. The Madhyamikas were so called on account

of the emphasis they laid on the middle view. Here, the middle

path, stands for the non-acceptance of the two views concerning

existence and non-existence, eternity and non eternity, self

and non-self. In short, it advocates neither the theory of reality

nor that of the unreality of the world, but merely of relativity.

It is, however, to be noted that the Middle Path propounded

at Sarnath by the Buddha had an ethical meaning, while that

of the Madhyamikas is a metaphysical concept.

The Yogacara

School is another important branch of the Mahayana. It was so

called because it emphasised the practice of yoga (meditation)

as the most effective method for the attainment of the highest

truth (Bodhi). All the ten stages of spiritual progress of Bodhisattvahood

have to be passed through before Bodhi can be attained. The

ideal of the Mahayana school, therefore, is that of the Bodhisattva,

a person who delays his or her own enlightenment in order to

compassionately assist all other beings and ultimately attains

to the highest Bodhi.

|

|