Intent,

in Tents and Intense

Abstract

The concept of Original Artistic Intent is difficult to apply

to Tibetan thangkas. Thangkas are composite objects produced

by painters and tailors with differing intents, skills and training.

Iconographic specifications, regional and doctrinal differences

in style, changes in form from harsh treatment and altered mountings

all complicate the issue.

Introduction

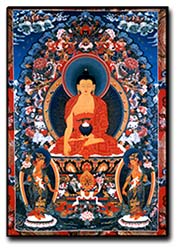

A thangka is a complicated, composite three-dimensional object

consisting of: a picture panel which is painted or embroidered,

a textile mounting; and one or more of the following: a silk

cover, leather corners, wooden dowels at the top and bottom

and metal or wooden decorative knobs on the bottom dowel.

Can you say that there was an artist who had a prevailing artistic

vision over the entire composition? Rarely. Is the thangka which

you are examining in your laboratory today in its original form?

Probably not.

Intent

What is the purpose of a thangka, what use was it originally

intended for? Thangkas are intended to serve as a record of,

and guide for contemplative experience. For example, you might

be instructed by your teacher to imagine yourself as a specific

figure in a specific setting. You could use a thangka as a reference

for the details of posture, attitude, colour, clothing. etc.,

of a figure located in a field, or in a palace, possibly surrounded

by many other figures of meditation teachers, your family, etc..

In this way, thangkas are intended to convey iconographic information

in a pictorial manner. A text of the same meditation would supply

similar details in written descriptive form.

Does the concept of artistic intent apply to thangkas? Only

rarely do thangkas express the personal vision or creativity

of the painter, and for that reason thangka painters have generally

remained anonymous as have the tailors who made their mountings.

This anonymity can be found in many other cultures.

There are, however, exceptions to this anonymity. Rarely, eminent

teachers will create a thangka to express their own insight

and experience. This type of thangka comes from a traditionally

trained meditation master and artist who creates a new arrangement

of forms to convey his insight so that his students may benefit

from it. Other exceptions exist where master painters have signed

their work somewhere in the composition.

The vast majority of anonymously created thangkas, however,

have taken shape as a scientific arrangement of content, colour

and proportion, all of which follow a prescribed set of rules.

These rules, however, differ by denomination, geographical region

and style. The Conservator is left with the responsibility of

caring for religious objects that usually carry neither the

names of the artists, nor information about their technique,

date or provenance. But we do know that the intent of the artist

was to convey iconographic information.

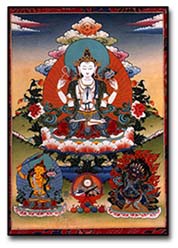

There is a vast amount of iconographic information provided

in thangkas, some of it literally spelled out for you. If you

look closely, many thangkas spell identification of figures

and scenes in formal and delicately rendered scripts. In damaged

sections of thangkas where paint layers are missing, letters

which indicate the master painter's choice of colour are sometimes

visible. These letters were not intended to be part of the final

composition and should not be confused with the former. But

given the breadth and variety of the iconography of Indian and

Tibetan Buddhism, it is virtually impossible to extrapolate

the information that would be required to fill in figures that

are missing or to complete the sacred objects that the figures

hold in their hands. Where inpainting is required, the definition

and clarification of artistic intent is a complex issue.

Since even indigenous Tibetan scholars trained in the iconographic

details of Buddhist deities generally would not presume to know

the iconography associated with every deity, it is unlikely

that most Conservators could guess the identity and details

of unfamiliar figures. In this case, speculation as to the artist's

intent tends to be a particularly unrewarding strategy.

In the twenty five years during which I have been working with

thangkas, I have chosen never to guess, calculate or presume

to identify missing iconographic facts. To do so would, in my

experience, contravene both the ethics that are required of

professional Conservators and the integrity of the objects that

have been entrusted to us. Even a subtle change in colour alters

the message of an icon.

For example, a particular shade of the colour green indicates

effective activity, while a white often indicates peacefulness

and unassailable compassion. It is significant therefore if

the same form of a feminine figure is rendered in green or white.

Is the colour you see before you the colour which the artist

intended for you to see? Sometimes water damage (yak-hide glue

is susceptible to water damage) washes away several fine layers

of pigment on final paint layers or shading layers. This damage

exposes either underdrawing or flat colours which the artist

never wanted you to see. Although some details may be present,

unless the artist has also left a notation as to the specific

colour (sometimes revealed by paint loss), an error would be

made if the Conservator were to reconstruct something in an

inappropriate colour.

Often, a combination of water-damage, greasy butter lamp soot

and smoky incense grit permanently alters the original colours.

Evidence of this is often seen at the edges where a mounting

has protected the original colours.

In Tents - How Tradition

Contributed to Damage

Damage was particularly likely given the tendency of Tibetans

to travel long distances in harsh conditions. Thangkas were

important articles of the tent culture of nomadic monastic groups

in medieval Tibet. It was not unusual for a group of scholars,

yogins and priests to travel by yak to distant regions, set

up tents, unroll the thangkas and serve the local people by

teaching before moving on to another area.

This was good for the people but intense for the thangkas! Rolling

and unrolling was, and still is, unavoidably damaging for thangkas.

Rough handling and damp walls damaged both the paintings and

their mountings, in medieval Tibet and today as well. I have

studied the handling of thangkas today in existing traditional

monastic settings. I was invited by the Abbot of a major monastery

on the Tibetan border to work with the monks on proper care

and handling of their thangkas. During the year, according to

religious holidays of the lunar cycle, specific thangkas are

removed from storage, unrolled, hung up in damp and smoky shrine

halls, and then taken down, stacked for rerolling and placed

back in storage. Storage consisted of airless tin trunks designed

to protect thangkas from rodents. The trunks smelled of bacteriological

activity.

The monks in this monastery value their thangkas. But rolling

and unrolling combined with rough handling and poor storage

constantly damages their treasured thangkas.

Intense

Now if you are feeling that the subtleties of colour and iconography

are overwhelming, we can continue on to style and technique!

If you feel that the original artists were working by a set

of rules to which you have little access, let us reinforce that

tense feeling by looking at the range of traditional styles

and painting techniques, which the original artists were guided

by. Then we will continue on to discuss the mountings which

were made by tailors who worked by a completely different set

of guidelines.

Paintings

Basic painting technique differs with regional style, training

of the artist and the funding available to purchase gold, expensive

pigments and so on. Also with the number of students or assistants

the master painter employed.

Did the artist contour areas of iconographic and non-iconographic

detail (such as sky or grass) with wet shading, dry shading

or a combination of the two techniques? The Conservator would

have to study thangka painting technique to understand. A good

way to recognise these techniques is by learning to paint thangkas

or by studying incomplete thangka paintings.

Did the artist apply many fine layers of paint one upon the

other, or one heavy layer? Regional styles differ in the technique

of paint application.

If the paint layers are lost and damaged, can the Conservator

judge the artist's intent from the surrounding areas? Should

the Conservator tone in lost areas of non-iconographic detail?

Private collectors and dealers, for example, often request a

Conservator to inpaint all damaged areas.

Although some of these questions are standard conservation issues,

they are further complicated when religious and iconographic

message must be respected and maintained.

Mountings

Thangkas are not only paintings. Their textile mountings are

very important. When dealing with the mountings, a new set of

questions arises. Did the artist of the painting have any control

over the style and proportions of the mountings which surround

the painting? Was the original choice of mountings that of the

patron or that of the tailor? Is the tailor to be considered

in a discussion of artist's intent? Was the painting created

in one part of Tibet and framed in another part of Tibet, China

or Northern India? Did the silk come from China or the Middle

East along active trade routes? Is the mounting done in a different

style, technique and aesthetic from those of the painting?

Is the silk brocade mounting currently part of this thangka

in fact the original mounting for this picture panel, or could

it be the third or fourth replacement? The answer to this last

question can often be found on the edges of the support where

several row of stitch holes can indicate that the mounting has

been changed.

Does the mounting obscure significant sections of the painting?

Tailors have been known to sew mountings with a window so small

that it covers important iconographic and aesthetically relevant

sections of the painting composition. The form of the mounting

therefore may alter the artist's intent by obscuring details

significant to the iconography and aesthetics of the painting.

Summary

The conservation treatment of a

thangka is a complex process that reflects the complexity of

the original composite object. All of the issues raised above

must be evaluated in deciding on the appropriate treatment for

a specific thangka.

For example, a Conservator must look carefully for any exposed

colour notations and not confuse them with iconographic lettering

on the final paint layers. A Conservator must evaluate what

regional and stylistic techniques were used in producing the

painting and mounting and also look for damage from past handling.

And finally, the Conservator must examine the current mounting

to determine its relation to the painting and document whether

it covers significant sections of the painting.

In summary, thangkas are complicated composite objects which

are designed to communicate iconographic ideas in a beautiful

and practical form. A thangka in your laboratory or collection

may be the production of many painters and tailors with differing

intents, and differing skills and training. The textile mounting

may have a completely different style, date and region of origin

from those of the painting.

Pure, single artistic intent is lost through a combination of

iconographic specifications, regional and doctrinal differences

in style, changes in form subsequent to the original creation

and many years of harsh treatment.

- Ann

Shaftel

Acknowledgments:

The Author

is indebted to the late Vajracarya, the Venerable Chögyam Trungpa,

Rinpoche, the late H.E. Jamgon Kongtrul, Rinpoche, and to Khenpo

Tsültrim Gyamtso, Rinpoche.

Copyright © 1993 by Ann Shaftel

Ann Shaftel is an Elected Fellow of the American Institute for

Conservation and the International Institute for Conservation.

She has published and lectured on thangkas and served as consultant

and conservator for monastic and museum collections for the

past 25 years. She holds an MSc in Conservation from Winterthur

(1978), an MA in Oriental Art History from the University of

Michigan, Ann Arbor (1972), and a BA from Oberlin College (1969).

She also studied at UNESCO-ICCROM. She apprenticed to Tibetan

master painters for 15 years.